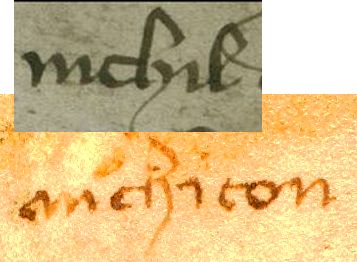

Here’s the latest on the Savoy palaeography post from a couple of days back: firstly, I donned my image analysis hat and went hunting for any sign of the missing “l”-loop. Enhancing f116v right to the edge, you can certainly just about make out a loop above the “t” of “michiton” (highlighted below), which would be consistent with the prediction that this word was originally “nichil”:-

Of course, I’d be the first to admit that what’s being enhanced here is probably not ink but rather a faint depression in the vellum, which may or may not be connected with the word. Hence, given that this is right at (or possibly beyond) the limit of what we can see in the Beinecke’s scans, it’s important not to get too excited – the right thing to do would be to wait until we can get a different kind of close-up scan of these details, so we can make proper concrete progress.

But in the continued absence of useful data that would settle this kind of question definitively (when will the Beinecke’s Kevin Repp respond to my requests?), here’s the wrong thing, i.e. yet more probabilistic speculation based on uncertain codicological evidence. 🙂

If this is “nichil” (or indeed “michi“), I think we can tentatively infer quite a lot. For a start, it would imply that this line of the text is

- probably written in Latin, specifically in what is known as “Ecclesiastical Latin”;

- probably after 1400 (which is roughly when Leonardo Bruni started advocating the use of “michi” and “nichil“);

- probably in Northern Italy or Southern France (which is where Bruni’s ideas spread the strongest); and

- probably in either an ecclesiastical or proto-humanist context (the two groups most influenced by Bruni).

Yet I would say that the handwriting seems less an Italian hand than a Southern French hand: and to back this up, I’ve been going through handwritten documents from 1350-1500 in the Archives Départementales de la Côte d’Or, in particular the “Recherches des feux des bailliages” (which I presume come from a hearth-counting tax assessment programme of the time). The records for Auxois contain documents from 1376-78, 1397, 1413, 1460, 1461, 1470 etc, so provides quite a nice vertical palaeographic slice of the archives:-

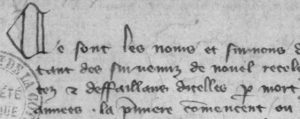

Auxois 1376-78: fol.2 – “Ce sont les noms et surnoms…“

Voynich researchers should immediately feel very much at home here: there’s the Gothic-y angular “l”, the “y”-like “p” (though closed rather than open), and “premiere” on the bottom line is even written with a generously overlooped “p” (as per the VMs’ Q1 quire number).

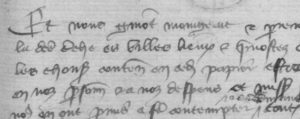

Auxois 1397: fol.221

Curiously, the 1397 record doesn’t seem to be as good a match to the VMs’ marginalia as the 1376-78 record…

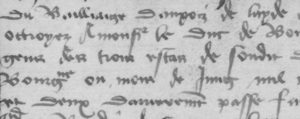

Auxois 1413: fol.2

…while the 1413 hand is I’d say an even worse match (and don’t even ask about the 1460 hand, that’s worse still).

So, the best matches to the handwriting in the VMs’ marginalia would seem to be from Savoy circa 1340-1380 (the previous post showed “nichil” written in a 1345 Savoy hand). Now, this kind of evidence isn’t quite enough to date the VMs on its own: but if we link it with the radiocarbon dating and unusual quire numbering, we might perhaps tentatively infer overall that circa 1425, this line of the marginalia was added (probably in Savoy) by an old monk (or possibly a humanist) who was probably from Savoy. All of which may not sound like much, but it might well yield a genuinely concrete step in the right general direction, let’s hope.

I’d be interested to find out what Voynich palaeographers make of this (*cough* Barbara): and if it is basically right, then perhaps Voynich researchers might now do well to start (1) finding archives containing Savoy letters and documents written circa 1400-1430, and (2) book resources on Savoy social networks circa 1400-1450. Who knows, perhaps we will find a letter by an old Savoyard monk or humanist with surprisingly similar handwriting, who knows? 🙂