Though Professor David A. King is best known, academically speaking, for his detailed study of astrolabes, I first ran across him via his epic (2001) tome “The Ciphers of the Monks” (summarised here): there, what happened was that one particular 14th century astrolabe from Picardy had some markings in an unusual number system first devised by Cistercian monks, and – like the proper devotee of historical arcana he assuredly is – King began collecting all the occurrences of that system he could find, which culminated in his book on the subject. There’s also a nice paper here on how the same number system was also used for tallying / gauging wines in the late Middle Ages.

All of which provides a suitable introduction to King’s most recent excursus beyond mainstream astrolabe history, because for this too the herald for his ‘call to adventure’ was an astrolabe with unusual markings on it (this time, an angel and an apparently acrostic dedication). But this second astrolabe also had a remarkable provenance – that Renaissance king of astronomers Regiomontanus had constructed it and presented it to his patron Cardinal Bessarion. Once again, David King set out to try to uncover the meaning of an astrolabe’s curious engravings – but his research journey carried him onwards to the artist Piero Della Francesca, right at the heart of the Renaissance project…

The angel part of the astrolabe engraving looks straightforward enough (note the parallel hatching on the top wing-edges, the trendy crosshatching in the background, the mid-Quattrocento “^” for “7” in the 60/70/80/90 sequences, and the early-Quattrocento ‘4’ shape at the bottom):-

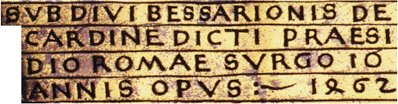

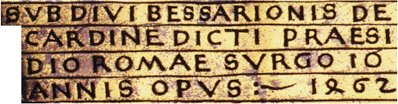

Similarly, the dedication looks straightforward enough too at first glance (note the looped early-Quattrocento ‘4’ in 1462):-

SVB DIVI BESSARIONIS DE

CARDINE DICTI PRAESI

DIO ROMAE SVRGO IO

ANNIS OPVS :~ 1462

King translates this as: “Under the protection of the divine Bessarion, said to come from the cardo, I arise as the work of Ioannes in Rome in 1462“. But the clever part, King believes, is that Regiomontanus’s slightly clunky Latin manages to cleverly conceal a number of additional messages to his new patron Bessarion:-

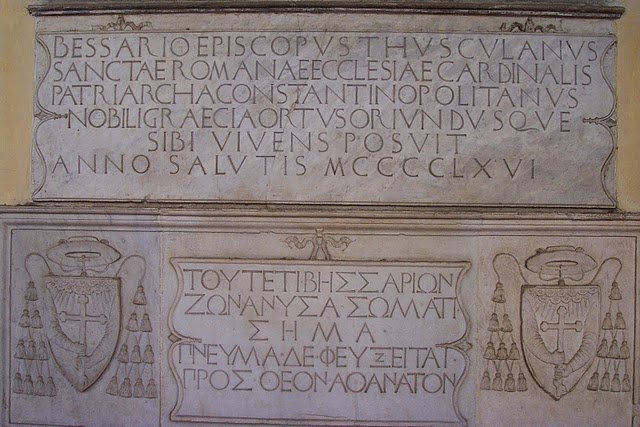

Here eight hidden vertical axes of an acrostic contain all sorts of hidden messages that would have especially pleased the Cardinal once he had figured them out: references to himself and his rank, to Regiomontanus, and to an old Byzantine astrolabe that he had shown to the young German. The angel is Bessarion, but not the Cardinal. There are several plays on the Latin word cardo, meaning “hinge, axis or pole”. In brief, two astrolabes come together in one, two poems, two languages, two Bessarions, two men who used the name Ioannes, two places, Rome and Constantinople, all come together in one.

Ummm… eh? It’s just a dedication, isn’t it? When I first looked at it, all I really noticed was the word “DEI” vertically hidden at the end: but Professor King thinks that the wobbly spacing and stretched letters indicates that there is much, much more going on here. However, it has to be said that after it was auctioned by Christies in 1989, precisely the same evidence was used to argue that it was “suspicious”, and that it even might be a “19th-century fake”: so be aware that we are now entering the kind of is-it-a-cipher/is-it-a-hoax territory that should be eerily familiar to Cipher Mysteries readers…

The other thing you need to know is that Bessarion also owned a spectacular Byzantine astrolabe dated 1062, which also had “:~” on one of its engraved bands of text: King agrees with Berthold Holzschuh that the two astrolabes are connected in some way, and that perhaps part of the reason for Regiomontanus’ presenting it to Bessarion in 1462 was to mark the 400th anniversary of the making of the magnificent Byzantine astrolabe.

So, let’s take a deep breath and dive deep into King and Holzschuh’s acrostic world, to see if his theories hold water (or if they sink like a stone)…

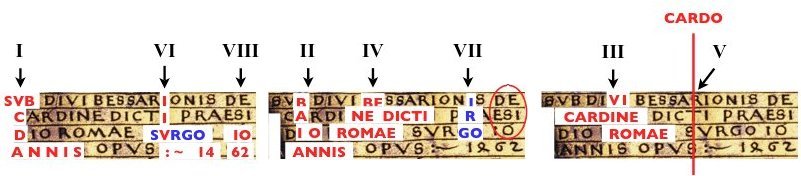

Firstly, Holzschuh suspects that the primary secret message held here emerges if you reorder the words to mirror the start of the Greek text on the Byzantine astrolabe:.

SVB BESSARIONIS PRAESIDIO

SVRGO

IOANNIS OPVS DICTI DE CARDINE DIVI

ROMAE 1462

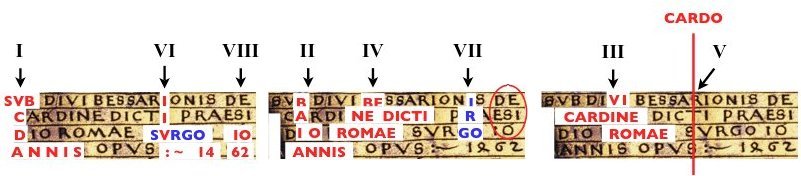

…which (because the Latin word ‘cardo’ means hinge or axis) he translates as “Under the protection of Bessarion, I arise in Rome in 1462 as a work of Ioannes explaining the rotation of the universe“. He also notes that the angel’s fingers “point to 4 and 8 hours on the horizontal scale of the markings below it, suggesting we should look for eight items in the four lines of the epigram“. The eight vertically hidden messages he highlights look like this:-

(Note that this is adapted from p.12 of David King’s Regiomontanus theory webpage, but that the DEI ESIO (‘ESIO TROT‘, surely?) acrostic ringed in red was mislabelled VIII).

Now, I have to say that I really am particularly impressed with the acrostics marked I (SVB CD ANNIS) and VIII (1062 / 1462), in that these not only tie in neatly with the “:~” on Bessarion’s 400-yearold Byzantine astrolabe, but also nicely explain (a) the curious starting position of “SVB” on the top line and (b) why IOANNIS is split over two lines. However, sorry to be a dreadful cipher party pooper but I don’t actually buy into a single one of the other acrostics suggested, nor into any of the hundreds of tenuously complex patron saint / birthday / symbolism / IO / 1407 / golden section etc arguments that are used to support them. No, not even the angels’ fingers.

To my eyes, the astrolabe’s acrostic angle does tell a hidden story: that Regiomontanus presented this to his patron in 1462 with a silent nod to the 400th anniversary of Bessarion’s Byzantine astrolabe. Perhaps there’s even “DEI” hidden on the right (though this seems way too prosaic and straightforward for the needs of King’s complicated exegesis). However, I honestly don’t see any evidence of anything else hidden in the message that is beyond pure chance, i.e. that you could not also extract from just about any other Latin inscription of comparable size and date.

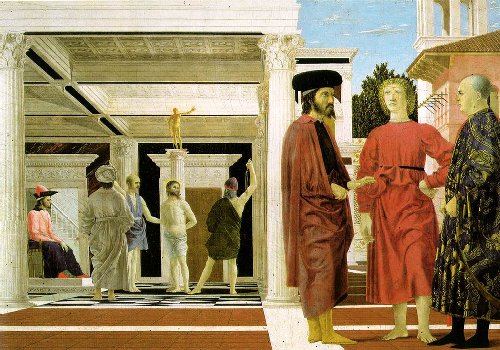

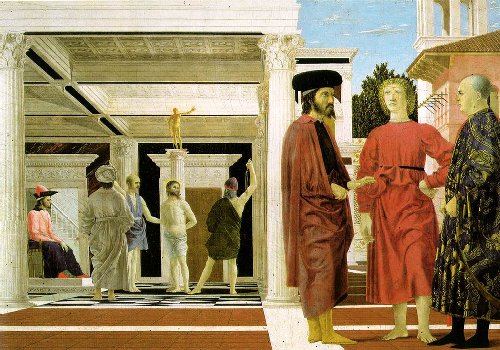

Hence, I just can’t make the giant leap over to the second plank of King’s narrative, which connects Bessarion’s patronage of Regiomontanus (as expressed in the 1462 astrolabe) to Piero Della Francesca’s epic painting “The Flagellation of Christ“, which Martin Kemp (1997) rightly described as “sumptuously planned”. This single work has caused more art history ink to be spilled in vain than perhaps any other painting (yes, even more than the Mona Lisa): King tabulates (pp.23-24) over forty subtly nuanced theories about who the various characters represent, before adding Berthold Holzschuh’s (2005) theory to the list – that the bearded man at the back being whipped is Cardinal Bessarion, and that the man in red at the left of the foreground group is Regiomontanus.

Nope, sorry – this theory doesn’t work for me either. There’s maths and geometry aplenty in Piero’s work, sure, but I completely fail to see how it links to Bessarion and Regiomontanus on any level. Perhaps my idea of what constitutes evidence is just too limited, or maybe I’m just too stupid to grasp how these two objects do really form part of a vast Renaissance patronage fugue. 🙁

If, however, you’re still intrigued by all this, there’s a nice set of slides on King and Holzschuh’s theory here: and a 2007 book by David King on the subject, with the snappy title Astrolabes and Angels, Epigrams and Enigmas – From Regiomontanus’ Acrostic for Cardinal Bessarion to Piero della Francesca’s “Flagellation of Christ” (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner) that you can buy on Amazon, though be warned that even a second-hand copy is a hefty £120 (yes, really!) Enjoy!