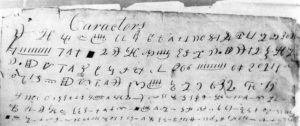

Here’s a thing that struck me the other day about the Anthon Transcript that I thought I ought to mention.

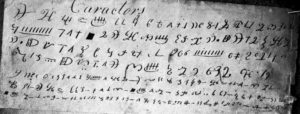

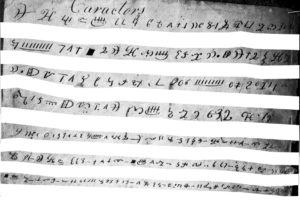

The way that the story has been passed down to us makes it far from easy to reconcile the “Caractors” page…

…with the “singular scrawl” shown to Professor Charles Anthon in 1828:

“It consisted of all kinds of crooked characters disposed in columns, and had evidently been prepared by some person who had before him at the time a book containing various alphabets. Greek and Hebrew letters, crosses and flourishes, Roman letters inverted or placed sideways, were arranged in perpendicular columns, and the whole ended in a rude delineation of a circle divided into various compartments, decked with various strange marks, and evidently copied after the Mexican Calendar given by Humboldt, but copied in such a way as not to betray the source whence it was derived.”

It would seem as though the first page was arranged in horizontal rows, while the second page was arranged in vertical columns and with a compartmentalized circle added after it. It sounds as though we are talking about two quite different things, and so shouldn’t even attempt to reconcile them as one. Yet in the decade up to his death in 1888, David Whitmer repeatedly asserted that this first page was indeed the very same “original paper” that Martin Harris had taken to Charles Anthon.

At this point, any passing Intellectual Historian might gently suggest that all these statements may well have been said in good faith: and that what is actually stopping us seeing them all as descriptions of the same thing is not the evidence itself, but our stubbornly persistent misreading of what is in front of our faces.

Can we do better?

The case of the ‘H’

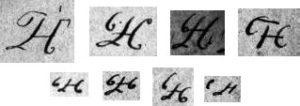

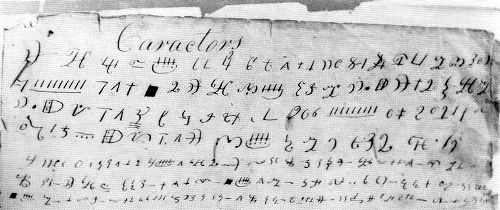

I suspect that we can: and the giveaway that may well help to point us in the direction of what happened is the capital ‘H’ shape that occurs at least eight times:

How on earth did the person copying this down not notice that this was nothing more than an ornate ‘H’ shape? Though I’ve long wondered about this, reasonable answers have to date always eluded me. But what I noticed here is that perhaps the actual explanation is painfully simple: that the person who originally wrote these down copied the shapes as if they were written in columns, i.e. without seeing them as ‘H’ shapes at all.

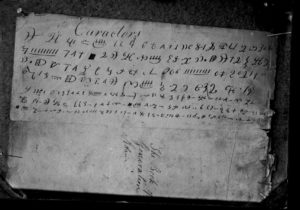

The photograph in Clay County Museum directly supports this idea, because the writing on the other side of the fold (“The Book of Generation Adam”) is written sideways:

The two-button mouse

Even though most of the Caractors are evenly inked, the strong downward strokes of one of the three “two-button mouse” shapes also seems to indicate to my eyes that the letters were written ninety degrees rotated from what we see now (though I’d appreciate other people’s palaeographical insights on this particular issue):

I’d have thought the suggestion that these letters were originally written in columns rather than rows would be a palaeographical hypothesis that could be tested out and resolved one way or the other.

Reconstructing the sequence

If the above is basically right, it would seem that the stages that this page went through were:

(1) The shapes were copied in columns from a source that was (wrongly) believed to have also been written in columns.

This caused letters such as the ornate ‘H’ shape to be copied not semantically as letters, but instead as a series of strokes. I would also expect that these columns were copied downwards as per the following image:

I can see how someone who had not grasped the correct orientation of these letters might have considered their rotated versions to be “hieroglyphic”-like. (I can also see how going from “hieroglyphic”-like to reconstructing the 2500 B.C. Jaredite flight from Egypt to America in submarines might seem a little too extreme for some.)

Note that I can easily see how the bottom of this page (beneath the ragged fold in the museum photograph) could have originally contained a “rude delineation of a circle divided into various compartments”: in which case the page was obviously longer. The overall page was also probably folded in half (parallel to the longest edge) at around this time, because only a single crease is apparent in the photograph.

This, then, would have been what was shown to Charles Anthon in 1828.

(2) The circular calendar section was removed, and the ‘Caractors’ word added.

Note that MacKay et al [*1] showed that the “Caractors” lettering at the top and the lettering of the curious letters were all done in the same ink. However, it also seems likely to me (from the orientation) the Caractors word was added in a quite separate construction phase, and their conclusion that this word was added at the same time as the rest of the letters ought to be examined very carefully indeed.

I believe that the circular calendar section was removed around now because of the following phase…

(3) The “Book of Generation Adam” text is added circa 1830, halfway down the reverse side.

Because this text was added right in the middle of the reverse side, it seems likely to me that the circular calendar section had already been removed (or else this text would probably have appeared further up the [slightly longer] page).

We can date this addition to 1830 or after, because that is when the phrase “The Book of Generation Adam” began to be used in the Mormon Church.

(4) The “Book of Generation Adam” half of the page is removed before 1884.

As Grindael noted, the part of the page with the “Book of Generation Adam” text was almost certainly “torn off sometime before 1884, because it is described as having the same dimensions then as it did in 1903”.

(5) The remaining fragment is sold to the RLDS Church in 1903.

“This collection of documents [was] eventually given into the care of George Schweich, a nephew of David J. Whitmer, who subsequently sold them to the RLDS Church for $2450 in 1903.”

Is this sequence correct?

I don’t honestly know. But if you were to try – while wearing an Intellectual Historian hat – to reconcile what you see in the RLDS Caractors fragment with the different testimonies assuming they were all given in good faith, then I strongly suspect that this sequence is extremely close to where you would necessarily end up.

And perhaps that’s as good as it gets, at this distance in time. Or… perhaps this is just the start?

[*1] MacKay, Michael Hubbard; Dirkmaat, Gerrit J.; Jenson, Robin Scott. The “Caractors” Document: New Light on an Early Transcription of the Book of Mormon Characters – Mormon Historical Studies, vol. 14, No. 1.