Every few years, I get around to posting a list of Voynich challenges – things about the Voynich Manuscript that we would like to know or to find out.

Looking back at my 2001 list of Voynich Challenges, I seem to have been flailing around at every codicological nuance going: yes, there are hundreds of interesting angles to consider – but how many stand any chance of yielding something substantial? With the benefit of just a little hindsight, I’d say… realistically, almost none of them (unfortunately).

Stepping onwards to my 2004 list of Voynich research tasks, which was instead mainly focused on a particularly narrow research question – whether Wilfrid Voynich lost any pages of the VMs. (Having myself consulted the UPenn archives in 2006, I’m certain the answer is a resounding ‘no’.)

Also in 2004, the release of the (generally excellent) MrSID scans by the Beinecke Library (even though it carried out test scans in 2002) was also an important landmark for study of the VMs, because it allowed anybody to look closely at the primary evidence on their own PC without having to trek to New Haven. Many old questions (particularly about colour) that had bounced around on the original VMs mailing list for years were suddenly able to be answered reasonably definitively.

Hurling our nuclear-powered DeLorean fast-forward to June 2009, what things do we now want to know? And moreover, even if we do find them out, does any of them stand any chance of helping us?

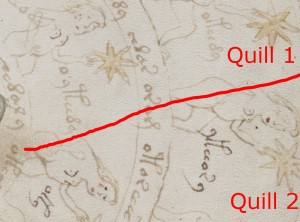

For all the determined work over the years that has been put into trawling the post-1600 archives (particularly Kircher’s correspondence), I can’t help but think that there can be precious little left to find of significant value. It has been a nice, well-defined project – but can I suggest we put it behind us now? The presence of 15th century handwriting (on f116v) and 15th century quire numbers surely makes this avenue no more than a fascinating diversion, no more useful than a forensic dissection of (say) Petrus Beckx’s life. Ultimately, “what happened to the VMs after 1600?” is surely one of the many convenient (but wrong) questions to be asking.

But what, then, are the right questions to be asking? In my opinion, the seven most fruitful historical research challenges currently awaiting significant attack are the following…

(1) Understanding the ownership marginalia on f1r, f17r, f66r and f116v, in particular what caused the text on them to end up so confused and apparently unreadable – even their original language(s) (Latin, French, German, Occitan or Voynichese?) is/are far from certain. Whatever details turn up from this research (dates, names, places, languages, etc) may well open the door onto a whole new set of archival resources not previously considered. Alas, delayering these marks is just beyond the reach of the Beinecke’s scans – so unless our Austrian TV documentary friends have already deftly covered this precise angle (and I’m sure they are aware of this issue), I think this would be a fantastic, relatively self-contained codicological / palaeographic research project for someone to take on. Do you know a Yale codicologist looking for a neat term project?

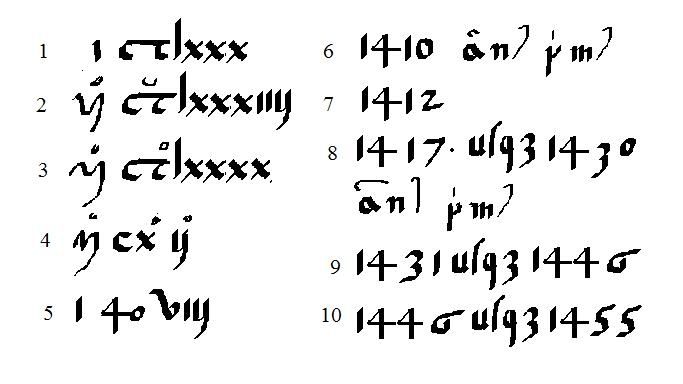

(2) Palaeographically matching the VMs’ quire numbering scheme – abbreviated longhand Roman ordinals (but with Arabic digits for the most part). Again, this should be a self-contained palaeographic research project, one that a determined solo investigator could carry out (say) just using the British Library’s resources. Again, if this suggests links to documents with reasonably well-defined provenances or authorship, it may well open up an entirely new archival research angle to pursue.

(3) Examining the “aiiv” groups for steganography, both in Currier A and in Currier B. I’ve made a very specific prediction, based on carefully observing the VMs at first hand – that in the Herbal-A pages, the “scribal flourish” was added specifically to hide an earlier (less subtle) attempt at steganography, based on dots. A multi-spectral scan of some of these “aiiv” groups might well make reveal the details of this construction, and (with luck) cast some light on the writing phases the author went through. Definitively demonstrating the presence of steganography should also powerfully refute a large number of the theories that have floated around the VMs for years.

(4) Reconstructing the original bifolio nesting of the VMs. Glen Claston and I have attempted to do this from tiny codicological clues, but this is in danger of stalling for want of applicable data. But what kind of data that could be collected non-destructively be useful? Ideally, it would be good if we could perform some kind of DNA matching (to work out which bifolios came from the same animal skin), as this would give a very strong likelihood of connecting groups of pages together – and with that in place, many more subtle symmetries and handwriting matches might become useful. Would different animal skins autofluoresce subtly differently? I think there’s a fascinating research project waiting in there for someone who comes at this from just the right angle.

(5) Documenting and analyzing the VMs’ binding stations. If the VMs happens to go in for restoration at any point (which the Beinecke curators have mentioned at various points as being quite likely), I think it would be extremely revealing if the binding stations and various sewing holes on each bifolio were carefully documented. These might well help us to work out how the various early bindings worked, which in turn should help us reconstruct what early owners did to the manuscript, and (with luck) what the original ‘alpha’ state of the manuscript was.

(6) Carefully differentiating between Currier-A and Currier-B, building up specific Markov-like models for the two “languages”, and working out (from their specific differences) how A was transformed into B. This may not sound like much, but an awful lot of cryptological machinery would need to rest on top of this to make any kind of break into the system.

(7) Making explicit Glen Claston’s notion of script & language evolution over the various writing phases. This would involve a combination both of palaeography and statistical analysis, to understand how Voynichese developed, both as a writing system and a cryptographics system. There’s a great idea in there, but it has yet to be expressed in a really detailed, substantial way.

In retrospect, a lot of the art historical things that preoccupied many Voynich researchers (myself included) back in 2002-2005 such as comparisons with existing drawings, the albarelli, etc now seem somewhat secondary to me. This is because we have a solid date range to work with: the Voynich Mauscript (a) was made after 1450 (because of the presence of parallel hatching in the nine-rosette page), and (b) was made before 1500 (because of the presence of two 15th century hands, in the quire numbers and on f116v).

Some people (particularly those whose pet theories don’t mesh with this 1450-1500 time frame) try to undermine this starting point, but (frankly) the evidence is there for everyone to see – and I think it’s time we moved on past this, so as to take Voynich research as a whole up to the next level. Though researchers have put in a terrific amount of diffuse secondary research over the years, collectively our most productive task now is to forensically dissect the primary evidence, so as to wring out every last iota of historical inference – only then should we go back to the archives.

Will these seven basic challenges still all be open in 2012, a hundred years after Wilfrid Voynich claimed discovery of his eponymous manuscript in a Jesuit trunk? I sincerely hope not – but who is going to step forward to tackle them?